Typically, most arts conferences that I attend do not include water-pouring ceremonies, pop-up coloring sessions, or group meditations. Yet not all conferences are created equal, and I recently participated in one that included all of those activities–and then some.

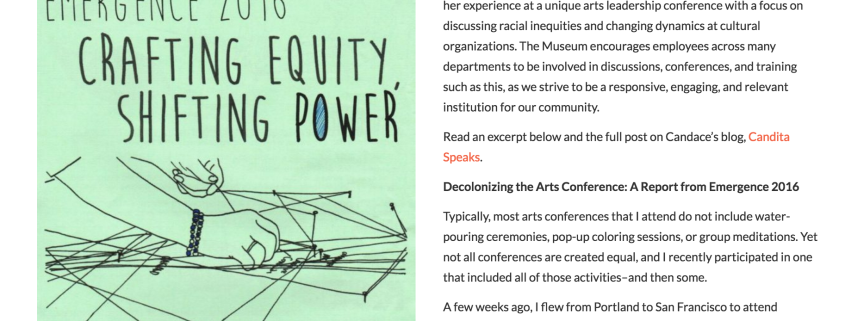

A few weeks ago, I flew from Portland to San Francisco to attend Emergence 2016, the annual convening of Emerging Arts Professionals San Francisco/Bay Area. Like many conferences, Emergence seeks to connect arts and culture workers to one another to share ideas and best practices for our field. Unlike many conferences, however, Emergence is grassroots, experimental, organized predominantly by people of color, and eager to tackle topics like revolution and justice, which were at the center of this year’s theme, “Crafting Equity, Shifting Power.”

As national demographics change and conversations on race, gender, class, ability, language, and more bubble to the surface of the arts sector, equity has become a hot topic for our field. As a person of color and member of Portland Emerging Arts Leaders’ Equity Committee, which seeks to spark dialogue and action surrounding cultural equity in Portland’s arts sector, I was eager to spend quality time at Emergence brainstorming ways to make our arts institutions less “male, pale, and Yale,” in the words of former Brooklyn Museum director Arnold Lehman.

Over the course of one day at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, coffee in hand and notebooks in tow, we asked difficult questions regarding power in the arts. Emergence focused on examining the practices, values, and assumptions that we tend to make within arts organizations. How did our current systems came to be? Who benefits? How can we create change? Breakout sessions like “Unpacking Privilege” and “Diversity is for White People: Arts Equity Conversations We Should Be Having” sparked provocative insights about ourselves and our institutions. Bay-area collectives such United Playaz and the Oakland Creative Neighborhoods Coalition shared on-the-ground creative tactics they are using to dismantle historical inequities. Plus, activities like personal creativity mapping and the Living Altar (“a drop-in space offering facilitated centering practices, one-on-one practitioner support, and healing circles”) challenged traditional models of learning and knowing, illuminating that there are ways of working that most “professional” spaces do not recognize or value.

At the end of the day, all 100+ conference attendees came together for one final large-group workshop, “Crafting Our Cultural Equity Frame,” facilitated by Dia Penning. It was this session that left me with the most revelatory takeaway from Emergence: that simple fact that many arts organizations operate–and indeed benefit—from a legacy of colonialism, Eurocentrism, and white supremacy.

We began the workshop by taking a deep dive into historical texts that justified European colonization of Africa, Asia, and the Americas beginning in the sixteenth century. Conquest, domination, and exploitation were primarily driven by desires to ensure European economic prosperity on a competitive global stage; to realize “the White Man’s Burden” and “civilize” non-white “savages”; and to investigate and exploit cultural “others.” Colonialism allowed European countries to completely reshape global economic relationships, ensure wealth systematically funneled to the colonizers, and ultimately gain world power.

Then, in a moment, that had the weight of a mic drop, Penning asked the toughest question of all: How are these colonialist values mirrored in the workings of your own arts organization?

After a few seconds of silence following this question of tremendous magnitude, we collected our thoughts and began discussing. Looking at the arts through a colonialist lens was a challenging but valuable frame to wield; while the interests of arts organizations seem far-removed from those of colonial empires, it is impossible to deny that colonialist thought has a legacy that still impacts us today. Looking at the origins of museums, their motivation to collect and possess objects to which they assigned value aligns with colonial strategies of resource hoarding and wealth-building. They readily built upon a curiosity that exoticized objects of non-white cultures, removed them from their cultural context, and served as “an edifice for the display and affirmation of bourgeois values” according to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu.Current conflicts around diversity and the clear lack of leadership of color at museums across the country also speak to an type of institution that has historically been white-dominant.

Despite these stark realities, we are not forever stuck in them; at the end of the workshop, Penning asked us to consider how we might change these systems and paradigms. At their most equitable, museums can hold the stories and histories of all peoples, preserving them for the future, and I am happy that there are endless examples of organizations and individuals striving towards that vision. My own institution, the Portland Art Museum, has catalyzed discussions about race, history, and power by increasingly highlighting work from groups who have historically not been represented in the institution, especially Native communities. Blogs like the Incluseum are sharing methods and practices to create diverse pathways for individuals to access and participate in museum life. Groups such as Museum Hueare sparking more conversation than ever before about how to dismantle the walls that have historically left many outside of collecting institutions. Our organizations, assumptions, and values are in a time of transformation.

We ended the workshop with the aforementioned water-pouring ceremony, calling on our ancestors to guide us as we reflected on the day. As the attendees trickled out, my brain was spinning with more questions than answers. The arts sector is astoundingly complex in its systems, history, and worldview, but to look at our field, we can start by looking at our organizations. These are some of the questions that I left with, which I encourage you to ask them of yourself and your organization, too:

- Who makes decisions?

- Who decides value?

- Who has power and why?

- How might you and your organization perpetuate a legacy of colonialism?

- What are you and your organization willing to risk to be more equitable?

During my flight back to Portland, I surveyed my notes from the conference, knowing that these are questions that I will continue to explore at the Museum and through my work with the PEAL Equity Committee. Reshaping power and cultivating equity are not easy, and they take time. However, even if they seem like gargantuan tasks, we can begin with small steps. Perhaps suggest that your next staff meeting include a grounding meditation and see what happens from there.

This blog post was originally featured on the Portland Art Museum blog by employee, Candace Kita. EAP is thrilled to share this write-up of Emergence 2016 with our readers!