By Alison Konecki, EAP Fellow

The issue

I remember being a college freshman, listening to everyone introduce themselves and their major (the latter of course being a seemingly crucial component of any introduction at the time), and thinking to myself how lucky I was to be responding “art history.”

My job was to study the world’s innovators, creators, beauty makers, thought-provokers, and doers! My very bones vibrated with the sheer thrill of it. Let the political science majors have their policy debates, and the finance majors fuss over bulls and bears. My work would be steeped in the things that made life beautiful and wondrous.

Although my complete naïveté didn’t persist much beyond the first semester (and thankfully so, I discovered, when my career landed me knee-deep in the world of non-profit arts), I had no idea its lingering fragments were yet to meet their greatest match.

Gentrification.

Having lived and worked in Washington, D.C. while bearing witness to gentrification’s wildfire sweep across broad swaths of the city over the course of a mere three years, I was no stranger to the term and its significance. However, until recently, I had only thought of the arts as one of a number of victims left bobbing and scrabbling for air in gentrification’s mighty wake. It wasn’t until the matter was turned thoroughly on its head – the arts as harbingers of gentrification – that my naïve notion of the arts reaping only positive effects was truly pulverized.

It came as a question: “What are your thoughts on the fact that the work you do [in the arts] can, and often does, lead to the displacement of communities and cultures?” (I paraphrase slightly, only because my surprise at the question left me feeling rattled and subsequently unable to recall the exact wording).

What were my thoughts? It was certainly true that artists were often the forerunners in up-and-coming neighborhoods. In fact, when advocating for greater arts funding, my go-to practical argument had always been that the arts create a robust economy – where the arts go, restaurants, shops, and residents were sure to follow.

And there it was, staring me in the face – the flipside to art’s ripple effect.

Although suddenly so clear to me, what was less clear was what was to be done. Cutting off arts funding and growth at the knees (god forbid) wasn’t the answer, but neither was playing naïve. I fumbled through an awkward response as I rolled these two extremes around my brain, desperately hoping an intelligent response would eventually emerge from my babbling lips. Alas, this did not occur.

Compounding my confusion was KQED’s Forum program “How Much Tech Can San Francisco Take?” I stumbled upon only a few days later. The program examins the rapid rise of the tech industry in the Bay Area, with critics arguing that “the trend and its accompanying high rents [are] shutting out artists . . . and threatening the very soul of the city.” The soul of the city. Yes! On went my rosy arts specs again. The arts are the soul of a city – not just in San Francisco, but in all cities, with each arts community a unique product of the particular city/neighborhood/enclave of which it is a part.

That was it. I was determined to explore art’s role in gentrification so that I could approach the issue with deeper understanding: with eyes open, yet hopefully still slightly tinted with the rosy hue emanating from a firm belief that the arts ultimately have a great life-enriching capacity.

Exploring the issue, one organization at a time

Approaching gentrification as a matter unique to each community that it affects, I began my exploration with a specific organization and community with which I already had a great deal of familiarity.

Sitting from my perch in the loft of Transformer, the non-profit gallery where I worked during my time in D.C., I was able to see a broad pageant of humanity walk past and peer into the gallery’s storefront window on any given day. Transformer’s executive and artistic director often remarked that the beauty of the space’s location meant a daily audience running the gamut from hipsters on their way to see a show at the divey music venue up the street, to homeless women and children staying at the shelter two blocks away, to Lululemon-bedecked yogis attending one of a half-dozen studios within a quarter mile radius, to clients on their way to the barbershop next door.

An interesting cross-section to be sure, but what did that mean?

By the time I arrived at Transformer, the gallery was already in its seventh year of operations, during which the neighborhood had undergone tremendous change. The nearest cross street, once rife with vacant lots and a multitude of abandoned buildings in various states of disrepair, had over the years proven a fertile space for clothing boutiques and restaurants to take root. True, “old” neighborhood holdouts such as the barbershop could still be found, but their number was far eclipsed by specialty food shops and trendy bars. Was the “interesting” mélange of people what that neighborhood envisioned for itself years ago? And where did Transformer fit in in all of this? A perpetrator? A soon-to-be victim? A mere witness?

Recently, Transformer, in partnership with fellow DC arts and community organizations Pleasant Plains Workshop and Artspace DC, held a panel discussion examining gentrification and its relationship to disappearing histories. The panel was full of great perspectives and ideas (too many to touch upon here – but click the link and watch an uploaded video of the panel!), but one thread of dialogue in particular resonated with me. The panelist Sylvia Robinson, Executive Director of Emergence Community Arts Collective, mentioned that “You can’t just truck in resources. You have to learn to work with the neighborhood, the culture that’s there.”

The key isn’t to parachute in with a mind to change/improve/save, but rather, to strive for equitable development. Whether an artist or arts space, you enter a community because you believe it has unique characteristics that will enable you and your work to flourish (mind you, I said it has, not it could have).

To wit:

Once, Transformer had a new potential funder stop by. Having recently moved into the neighborhood, this gentleman was intent on investing in his home turf. Excited for new-blood enthusiasm, we eagerly prepared for his visit with a private viewing reception complete with bubbly refreshments. He arrived, we popped the cork, and began talking about the current exhibition, when suddenly, with a quick slashing of his hand, we were interrupted.

“First,” he said, “we need to talk about your sign.”

Our sign? This man was standing amidst a tangle of brilliantly-colored sculpture seemingly defying gravity as it floated above our heads and he wanted to talk about our sign?! I will spare you the train wreck that ensued, but suffice it to say, he just didn’t get it. He thought we needed more flash. He didn’t see us as a worthy investment until we looked like a worthy investment. With all the amazing work we were doing to provide a space in which emerging artists had the breathing room to push the boundaries of their practice (not to mention the cost of doing that work), this gentleman had the chance to really make an impact furthering his community, and instead he was preoccupied with changing it.

True, our “sign” was merely a hand-stenciled “t r a n s f o r m e r” painted above the storefront. But our barbershop neighbors had a small hand-painted sign too, featuring mini portraits of each of the barbers painted by one of Transformer’s artists. There was quiet unity in that, and we were okay keeping it that way.

What does that mean?

At the time, I didn’t grasp the full significance of what happened at Transformer. Looking at it now through the lens of Ms. Robinson’s assertion that equitable development comes from within a community, I see that we were pushing back against the misguided notion of “improvement” that gentrification so often carries with it. It was a subtle protest to be sure, but an important one nonetheless. We couldn’t force that gentleman out of the neighborhood, but we could decide that we weren’t interested in accepting his “patronage.”

I still stand firm in my belief in the positive effects of the arts. However, I now offer a slight key amendment to that assertion: The arts are at their best when in service to their respective communities. Only then can they truly enhance our world through their powerful ability to provoke thought, challenge norms, and show us the beauty hovering otherwise unseen in the everyday.

***

Gentrification is an extremely complicated topic with many layers and viewpoints. It is our job as artists, and arts administrators and advocates, to work collaboratively with our respective communities to develop tailored, creative approaches toward equitable development. I haven’t nearly begun to scratch the surface in this discussion, so I invite you to check out the links below, and add your comments and suggestions so that we can grow this crucial dialogue.

About Alison Konecki

Alison Konecki is a freelance arts program and development consultant and a recent San Francisco transplant. She graduated with a B.A. in Art History and English from Canisius College in Buffalo, N.Y. and received an M.A. in Art and Museum Studies from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. During her tenure at Georgetown she spent a semester in London where she completed a course in Art and Business with a focus on contemporary art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. Prior to her move Westward, Alison was the development and community outreach coordinator for Transformer, a non-profit alternative art space in Washington, D.C., where she coordinated public programming initiatives including the organization’s Framework Panel Series, and assisted with development operations ranging from grant writing to donor cultivation. While in D.C., Alison also served as co-founder of Knowledge Commons DC – a free, self-generating “school” designed to provide non-traditional community learning and instruction.

Image: Adapted from photo by Sharat Ganapati

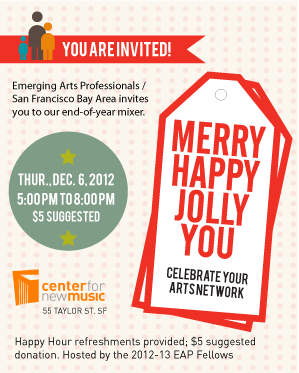

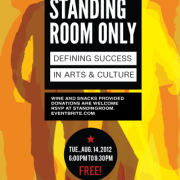

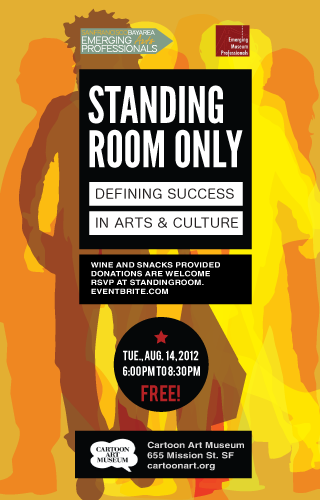

Emerging Arts Professionals / San Francisco Bay Area invites you to an evening of open forum discussion to assess where and how R&D fits into arts and cultural innovation.

Emerging Arts Professionals / San Francisco Bay Area invites you to an evening of open forum discussion to assess where and how R&D fits into arts and cultural innovation.