Recap: Net Art Anthology Launch

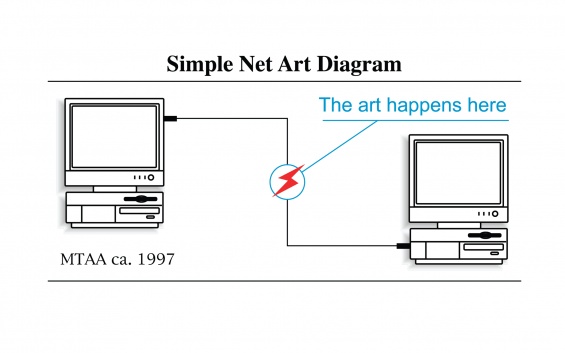

/0 Comments/in Recap, Uncategorized Tim Roseborough /by Tim RoseboroughOn October 27, Rhizome launched a major new initiative, Net Art Anthology, with a presentation and panel discussion bringing together a group of artists who championed distinct and often conflicting approaches to net art practice in the mid to late 1990s. Our new New York correspondent, SF/NY-based artist Tim Roseborough, was there to take it all in. Here’s his rundown…

Net Art Anthology Launch

Thursday, October 27, 7 PM

at the New Museum, 235 Bowery in NYC

Luminaries like New Museum curator Lauren Cornell and Internet artist Rafael Rozendaal were in attendance for an event organized in conjunction with the launch of Rhizome’s Net Art Anthology, an online exhibition which, in the organization’s words, hopes to “retell the story of Net Art.” The Anthology commemorates the 20th anniversary of Rhizome as a proponent and archive of Internet-based art practices and is funded by the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation.

Michael Connor introducing project

Michael Connor, Rhizome’s artistic director, introduced the Archive in which 100 Net-Based artworks will premiere, one a week, for two years. Mr. Connor’s introduction to the exhibition was accompanied by short talks by Aria Dean, assistant curator of Net Art and Dragan Espenschied, preservation director.

The panel consisted of artists who were involved in the early establishment of the field of Net Art in the 1990s: Olia Lialina (net artist and Geocities researcher/archivist), Martha Wilson (artist and founder of Franklin Furnace), Ricardo Dominguez (artist and founder of Electronic Disturbance Theater), and Mark Tribe (artist and founder of Rhizome).

Each artist discussed their early online work as artists, curators, and organizers. As well as some of the major issues faced and addressed by the organization and the world of Internet-based art, as a whole.

Mark Tribe remarked upon the fact that in the face of the Internet’s global reach, Rhizome’s New York-centricity was a problem. He noted that focusing on New York alone leads to, as he terms it, “navel gazing. In order to combat that myopia, Tribe described the site’s efforts to employ regional editors to chronicle the scenes in other cities. Martha Wilson noted that New York has always been a center for art and culture and that it was no surprise that Rhizome’s coverage and reach would reflect its status as such.

Ricardo Dominguez noted that Rhizome networks were broad, including cities like Vienna, Berlin, and Amsterdam, he noted the “teleportation” of the body that is facilitated by the broad reaching networks of the Internet.

The notion of the body and its mediation was a recurring theme at the panel. Martha Wilson discussed what she considered the myth of cyberspace as leaving the body behind. Regarding the ongoing conversation about the value of live performance art versus the importance of documentation of that performance, or the notion that “if it was not recorded, it didn’t happen.”

On Net Art’s relation to the avant-garde, Mark Tribe noted that like video art critiqued dominant forms like television, so Net Art can serve as a critique of the privatization of public space.

Olia Lialina noted that as a Russian artist, connecting with people abroad was an invaluable value offered to her as an Internet-based artist. She savored the fact that orders could be virtually crossed via the electronic superhighway.

Mark Tribe dismissed the notion that after After Modernism, art could explore no new avenues. The Internet opened new ways of making and thinking about art, according to the Rhizome founder.

The Rhizome founder also explained that the sense of excitement he felt when starting Rhizome in the mid-nineties is hard to recall. He noted that there was a sense of stepping across a threshold and into new frontier — much like the television show, “Star Trek,” he joked, eliciting laughter from the lively and engaged audience.

___________

Tim Roseborough, author of the artworldgeek.com blog.

Cultivating a Community with East Bay Center’s Jordan Simmons

/0 Comments/in Heart of It, MADE, Uncategorized /by Alex Randall Jordan Simmons is the Artistic Director of the East Bay Center for the Performing Arts in Richmond. Having grown up in Richmond and studied piano at the center when he was young, Jordan returned to teach there after earning a music degree from Reed College in Oregon. Jordan has been the artistic director and driving force of the center since 1985.

Jordan Simmons is the Artistic Director of the East Bay Center for the Performing Arts in Richmond. Having grown up in Richmond and studied piano at the center when he was young, Jordan returned to teach there after earning a music degree from Reed College in Oregon. Jordan has been the artistic director and driving force of the center since 1985.

The East Bay Center for the Performing Arts is a surprising place of discovery. Here our student artists— through the breadth, depth, and passion of experiencing classical master works and cutting-edge forms from around the world—come to know the world’s great performance traditions, the beauty of one’s neighbor, a calling in life, and the life of the mind, in addition to the spark of young imagination.

Through the active creation of original music, film, theater, and dance, coupled with self-determined community projects, we emphasize the cause of social justice, the hard work needed to prepare, the skills to create, and the courage to perform. We will soon open our completely restored building and with this new capacity, over the next 50 years, we plan to reach 75,000 more youth to carry on this work of discovery.

Jordan was interviewed by Jessie Dykstra, East Bay Fund for Artists Coordinator at The East Bay Community Foundation and a 2013-14 EAP Fellow.

JD: Let’s start with how you began your work with the Center and your transition to leadership.

JS: I was a student at East Bay Center when it first opened following the assassination of Dr. King. In 1978, after graduating from college, I came back to Richmond, and was hired as a faculty member by my former teacher – Richard Letts – who was at that time the Center’s general director.

During that period, the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA) was alive, and there were a series of police brutality suits in Richmond that had a huge impact on the community. One of the first things that I understood at that time – as both a very personal and a larger life lesson – was that we don’t control everything. In other words, communities like ours were vulnerable to external forces as well as historical forces.

Between ’78 and ’85, I went back and forth between Richmond and Salvador, Bahia doing field work with Brazilian musicians, activists and their communities. I worked in a neighborhood that was struggling to assert self-identify and self-determine their cultural values during the end of military dictatorship, all in light of historical issues with systemic violence and racial oppression. It was during a period that some called an abertura, or “opening.” So it was very important for me to see and to be part of what was happening in Salvador. Race, culture, class, art – all of these elements were part of the dialogue there in both a distilled and intense way.

East Bay Center hit a particular financial crisis in 1984. Following the police brutality suits and the loss of income to the cities from Prop 13, our income dropped. We also moved to the historic downtown area (where we are now), but downtown was a ghost town that was off-limits territory after dark. Suddenly there were no more middle class students coming here. So the budget ultimately went down from $400,000 to about $120,000, and we had back-taxes owed to the Federal Government.

There was also a struggle in those days (early 1980’s) to define the boundaries of a “community art” program. Society was asking: Who gets to study art? Whose art should be studied? Who should be teaching it? These questions were mixed in with our questions about: What do you do with young people when there are distractions in a society that is becoming more complex? What do we need from traditional art forms? And then what is the generative dialogue with the community? Some of these questions belonged to the time and some of them – it seemed – belong to the ages.

Ultimately, we came to understand that what the community needed and wanted interacted dynamically with what the faculty and artists of the Center had as a vision. And that dialogue has remained at the heart of what is a community-based organization – a generative engine of a program demanding attention to dialogue with its community.

JD: So what came out of that period of generation for you?

JS: We understood that the community wanted multiple things. They wanted a place where their children could practice arts that reflected their family heritage, but also try forms that reflected other heritages. They wanted youth to be able to find their gifts, but they also wanted to be prepared for the highest levels of academia and professional life. They wanted to find pride in place. They wanted to know and tell the stories of their families, of this neighborhood, and the conflicts and injustices of society here in this city. They wanted to see work that had production value and artistic depth, and they wanted to make their own art.

That dialogue drove the program structure that arose, and in that sense it also drove the jobs that people like me had to learn to do.

I was brought up to know literature and dramatic forms, to study certain kinds of music, and write and teach those things. But I certainly wasn’t prepared for the day-to-day issues of… well, I don’t even call it leadership. It’s the responsibility that my colleagues asked me to take on.

It’s like being part of a group that’s getting ready to eat together – somebody has to wash dishes, somebody has to go shopping for groceries, somebody chops wood, carries water, that kind of thing. You need to be useful – moving from principles and values into program ideas, moving from program ideas to exploration of what resources you have, and determining what you have to work with.

I’m very lucky that I’ve been able to see the evolution of the Center several times in these decades as things happened. In 2002, the bottom fell out again, and we went from one budget size to almost half. This was after growing for 17 years, following our path, creating works, telling the story of Richmond, adding curricular structure, being involved in the school district and working with them to promote public education. All those things had been growing for 17 years, and so that was an eye-opening point, remembering that we don’t control every thing. Humility, I guess.

When you’re forced to cut your budget or reduce your scale, you’re not just exploring and developing, but you’re making a stance about what’s worth saving and focusing on the things that represent those years of struggling and research and dialogue. For us, that became the Young Artist Diploma Program and the mission of engaging of young peoples through the discipline and inspiration of global art forms. The idea was not necessarily focused on getting to a conservatory level, but that through our program youth were gaining a vision of themselves and their community.

JD: So in reflecting back, were there specific roles that you felt like you played, things that you were learning individually as a leader?

JS: With our kind of mission, it always seemed to me that in order to be a leader, you had to be mindful of listening to community dialogue and trying to support that dialogue. And sometimes that meant taking criticism or developing a new vocabulary or language. It also meant being clear about the values of the institution, which meant sometimes saying “no” to some people. You try to advocate for the small decisions that support the larger ideals. So in that sense, I have always been challenged to keep in mind that all of us individually have to be strong, but collectively we have to keep going back to that dialogue. And that has become part of the culture of the institution.

Personally, I have continued to develop myself as a performer and teacher. In order to be part of the community dialogue honestly, I had to give whatever time I could spare to my own practice and teaching, my own growth and understanding. And that of course is an endless thing, but it keeps one young!

I would say the privilege I’ve been allowed was to be a representative of this group. There are folks in this organization who are my elders, like older brothers and sisters, and I have been asked to represent us wherever in the world I have to go, whether to West Africa to organize a performance, or the mountains of Mexico to research curriculum, or New York to plan with supporters. I have had to learn about the world and then come back. So that has been for me a challenge – and a privilege– to go out, try to distill those forces, and then bring them back to work out together.

JD: What would you say are the parts of the job you wish you could do all the time and the parts of the job you wish you didn’t have to do?

JS: I came back to the Center in 1978 to be teacher. Being a teacher also means being a student. As a teacher one is always growing, and when I have time for a class or a project, that is something I am most happy about. Being with young people is endlessly inspirational and beautiful.

I really enjoy now seeing the 30-somethings, that mid-generation of alumni who are returning here as faculty and staff to take up layers of responsibility. I really like seeing that the culture here is growing and changing and becoming more mature. It doesn’t have to fight the same battles we had to fight. It has new struggles to overcome – new challenges. I am watching those colleagues develop themselves and contribute to this community and institution. It’s exciting to see that the younger generation is building, broadly and deeply sinking their roots, and they then have new ideas.

JD: I’m curious to know what you are seeing right now in the Bay Area arts community, how you are feeling about working as an arts professional and where you see the community going from here?

JS: I actually have little to say about that! Maybe twenty years ago I did, when I had more bouncy energy. But I don’t really think of myself as an “arts professional.” I am striving to be a better musician and maker of theatre; I am striving to be a better teacher and student. And I’m really striving for the Center to have ever more integrity in what it does, that we accompany our young people where they are, and that we don’t compromise our values or integrity of artistic training. Maybe if we work on that really hard here, we can be a good example to other organizations.

I think society struggles with the difference between art as commodity versus the opportunity for every kid and every person to experience art and to discover their gifts, to have the time and wherewithal to participate in art and not just take it in through passive media. And I know there aren’t that many places that do work in that realm that continues to be heard. But I have no magic wand or crystal ball.

JD: So, it’s more about what you’re doing now versus trying to anticipate what may come next?

JS: Yes, there are a lot of smart people who have time to anticipate and show the trends and all of that. I think no matter how that happens that we want young people to value this complex environment and be ready for those changes that are happening both in art and institutions, in art production, art appreciation, art funding, or whatever it may be.

I remember asking one of my teachers many years ago what he thought about certain theoretical questions regarding intonation and scale. He looked at me and smiled and said, “Do you want a nineteenth century answer, the twentieth century answer, or the answer that’s coming?” By that he meant that over the ages we’ve had certain theories about major and minor scales, chromatic scales, and pitch, rhythm, timbre – and tried to decide which were sophisticated. And so we can make theories about these things, but in reality we’re all trying to be more human in our institution and more attentive to young people’s growth and discovery. And, I think we have to concentrate on that.

JD: I’ll close with this question: For the students in your community or anyone else who might be considering work in the arts, do you have any words of wisdom you would give them?

JS: Fundamentals are always good. And following your own calling – finding out what is your gift or your love. What’s calling you to work hard? Then take time to make the effort, because that effort is rewarding. We all want to be good; nobody has to try to want to be good. So, then you have you have to pay attention to what is really feeding you, so that you can go back to your fundamentals and strengthen yourself as an artist.

Be open to change and to the struggle of the tough times as well as the good times. And enjoy them because ultimately your evolution is a response to both.

There’s a quote, “Does the path choose the walker, or does the walker choose the path?” I don’t know, but the point is that every day we have to wake up and ask.

Jessie Dykstra is the coordinator of the East Bay Fund for Artists at the East Bay Community Foundation. She is also responsible for managing the Foundation’s scholarship programs and supporting the grants administration process. Before joining the Foundation Jessie was an institutional fundraising consultant with Quinn Associates, an arts management consultancy serving small and mid-sized organizations in the Bay Area. She previously held positions in Development at The Wooden Floor and the California Institute of Integral Studies. Jessie is a candidate in the MBA program at the Lokey Graduate School of Business at Mills College.

Cultivating a Community with East Bay Center’s Jordan Simmons is part of the series The Heart of It: Stories from Leaders in the Bay Area Arts Community, an EAP MADE Project. Learn more about the series by visiting the MADE page in our website.

Delving into Dance with AXIS’s Judith Smith

/0 Comments/in Heart of It, MADE, Uncategorized /by Alex Randall Judith Smith is the Artistic Director and Founding Member of AXIS Dance Company. Prior to becoming disabled in a car accident at age 17 in 1977, Judith was a champion equestrian. She transferred her passion for riding to dance after discovering contact improvisation in 1983. Under her direction AXIS has become one of the world’s most acclaimed ensembles of performers with and without disabilities. The repertory includes works by choreographers Bill T. Jones, Stephen Petronio, Yvonne Rainer, Joe Goode, Margaret Jenkins, Shinichi Iova-Koga, Victoria Marks, Ann Carlson, Remy Charlip, David Dorfman, Alex Ketley, Kate Weare and composers Meredith Monk, Joan Jeanrenaud, Fred Frith and Beth Custer and has received seven Isadora Duncan Dance Awards.

Judith Smith is the Artistic Director and Founding Member of AXIS Dance Company. Prior to becoming disabled in a car accident at age 17 in 1977, Judith was a champion equestrian. She transferred her passion for riding to dance after discovering contact improvisation in 1983. Under her direction AXIS has become one of the world’s most acclaimed ensembles of performers with and without disabilities. The repertory includes works by choreographers Bill T. Jones, Stephen Petronio, Yvonne Rainer, Joe Goode, Margaret Jenkins, Shinichi Iova-Koga, Victoria Marks, Ann Carlson, Remy Charlip, David Dorfman, Alex Ketley, Kate Weare and composers Meredith Monk, Joan Jeanrenaud, Fred Frith and Beth Custer and has received seven Isadora Duncan Dance Awards.

AXIS has toured throughout the nation, Europe and Russia and has been featured twice on FOX TV’s So You Think You Can Dance, bringing its genre of dance into literally millions of people’s living rooms. AXIS has been named a top 10 high-impact arts nonprofits in the Bay Area by Philanthropedia. The Company’s model education programs that offer a myriad of events for adults and youth of all abilities are highly regarded. AXIS is the primary organization that provides pre-professional training to aspiring dancers with disabilities. Judith was honored with an Isadora Duncan Dance Award for Sustained Achievement in 2014. In her spare time Judith is actively involved in thoroughbred racehorse rescue and carriage driving with her team of Percheron horses.

Judith was interviewed by Alex Randall, who currently works for BloomBoard, an education technology company, and was a 2013-14 EAP Fellow.

AR: What does being Artistic Director at AXIS encompass for you right now? What, what are your main responsibilities?

JS: Well, it’s changing. Up until this last year, I’ve been basically the Executive Director and the Artistic Director. So, my responsibilities have been fairly enormous and probably way too enormous. I now have a Managing Director who is as much or more responsible for some of the stuff that I was doing. At this point, I’ve been in this field of physically integrated contemporary dance for 27 years. I’ve seen the field grow and develop, and I would really like to be able to focus my energy on moving AXIS forward and moving the field forward and doing less of the everyday management.

Up until last year, almost everything was on me. I was the one responsible for developing the budgets, checking the books, and making sure things are getting entered right. Doing the HR, dealing with the visas, dealing with the contracts for consultants and finding the choreographers and dancers. It was mind-boggling, and now that I don’t have to do all of that, I kind of wonder how the hell I did all of that.

AR: Are there aspects of being an executive director that you’ve held onto because you really liked it?

JS: The things that I am focusing on are developing the artistic projects and grant language that goes around with those. And I definitely have to keep aware of the budget and finances, but it’s not on me to do it all. I don’t enjoy HR, and I don’t really enjoy that nitty-gritty management, so it’s nice to be able to let go of that. It’s nice to have someone else’s mind and voice and ideas on the development aspect and the communications aspect.

AR: Are there aspect of your work that serve as creative outlets similar to what performing has served for you in the past?

JS: Well, I actually love Excel spreadsheets, and I love developing budgets. I love getting really precise. I laugh because, this year, Karl and I only had four revisions of our operating budget, and usually, I have 14.

There can be a lot of creativity in how you budget, how you move money around, when you reforecast, and how you then again reallocate money. I also love the creativity of getting on the Internet and scouting for dancers and collaborators, finding out about somebody and figuring out where they really are.

AR: Do you feel like the shift you’re making right now is getting you closer to your dream job? Are you in it already?

JS: Well, definitely my dream job here, where I feel like I’m able to do things that I’m more effective at and not having to do things that I’m less effective at. My passion, from the time I had any concept of what anything was, was horses. So, if anybody ever asks me about my dream job, it would have been what I would have been doing had I not been disabled — showing jumping horses. You know, that’s just always there, but in terms of, you know, living my life as a disabled woman and a disabled lesbian, being in the arts and being in dance has been a great place to be.

I did get really burned out, to the point of fizzling over the last couple of years. Now, with this restructuring and the possibility of utilizing myself and my knowledge better, it’s resparked me and reinspired me, because there’s just so much that’s not done yet. And I still have a bucket list — we still have to get to ADF, there are a couple of choreographers that I still want to bring back, and there are a couple that we haven’t worked with yet.

AR: Are there people who have inspired you and kept you going along the way?

JS: Well, John Killacky has been a tremendous mentor to me. Victoria Marks, who is a choreographer, is just very smart. Sonya Delwaide — she was one of the first choreographers we commissioned, and she has done six or seven or eight pieces for us at this point, and she is also just really smart. KT Nelson — I bounce ideas off of her all of the time. Our bookkeeper, David Gluck, is somebody I rely on a lot. I think Bill T. Jones probably changed my life a little bit and really encouraged us to think about casting our net widely. This profession is so full of brilliant minds, really smart people who are really, really dedicated. It is nice to be a part of that.

AR: So, looking back, if you were to go back in time and give younger Judy, starting out with AXIS and realizing that you were going to be leading this organization, a piece or two of advice, what would they be?

JS: Run! Run! Run! Fast in the opposite direction. [laughs] Well, I will say that there were some mistakes I made starting out. I had really wanted this company to be co-directed. I did not make a great choice, and it took a few years to fix that problem because we didn’t have any of our organizational nuts and bolts. Like I said, we didn’t have an organizational chart. We didn’t have a job description. So, what I would tell that kid back then…I wish I had been able to be a little bit more direct and sterner when I needed to be and to find people sooner who could help me deal with problems.

I think you have to know a lot about this field, and that’s one thing that I did right. I wanted to know who the presenters were. I wanted to know who the funders were. I wanted to know who the patrons of the arts were. Where the venues were. Who the composers, choreographers, dancers, the people behind the scenes, lighting designers, stage managers were.

Just having a very, very broad scan of the field and knowing who’s out there and who you can go to. Go out and see everything you can, because that’s how you’re going to learn who’s out there. Read those programs.

Don’t be afraid to work hard. You know, it is kind of funny because, I do feel like I have accomplished a fair amount with AXIS, but it hasn’t been rocket science. It is not rocket science. It is a lot of fucking work, so just be prepared to know that you are going to be working 60, 70, and 80-hour weeks. If you are not able to do that, and if there is something else you can do that you will be happy doing, don’t do this. Just do this if you will shrivel up and die if you don’t.

The other thing is — be humble and gracious because you never know who’s going to be talking to whom. And be appreciative. Let people know you appreciate them and what they’ve done.

I wish I had reached out to people more who were doing this kind of work early on instead of looking at them as competition. I wish I had focused more on how we connect and help each other instead of feeling competitive. But, I’m sadly competitive and driven by nature. It’s something that I’ve really had to work on, which is why I love doing things like talking to you. I try to answer every email that comes in, even if I can’t help. I try to acknowledge it, you know? I don’t delete emails from random composer X from Serbia who wants to compose music for us.

AR: Is that a habit you started out with? Or is that something you developed over time?

JS: It’s definitely a habit I started out with. I started out when email was just starting, so not as many people were able to find you, but I really do try to be helpful when I can. I’m looking forward to having more time to do that because, over the past five years, I’ve had to say “no” to a lot of things that I wished I could do. This is the kind of stuff that I want to have more time for. I know a lot about physically integrated dance at this point, so it’s kind of dumb to sit with it in my head.

AR: That’s great! Well, I’m excited to hear what comes of that.

JS: Yeah, me too. We’ll see what happens.

##

Top Photo: Judith Smith and Janet Das in AXIS Dance Company’s Foregone choreographed by Kaye Weare. Photo by Andrea Basile.

Alex Randall, Director of Operations at BloomBoard

Alex Randall, Director of Operations at BloomBoard

Alex aims to bring arts and business communities together to celebrate the artists in all of us. He’s lived a tech/art double life for the last nine years, starting at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, CA, where he earned an engineering degree while dancing and acting on the side. Since graduating in 2010, Alex has worked for two education technology companies (one in Houston, on in SF), managing teams in business analysis, recruitment, account management, and customer service. In his evenings and weekends, he has performed with dance and theater companies, organized festivals (included the 2012 and 2013 Houston Fringe Festivals), covered dance for an arts publication, and volunteered with a number of art organizations (including Houston’s Business Volunteers for the Arts program and SF’s SAFEhouse for the Performing Arts). When he’s not busy with work or the performing arts, Alex enjoys creative writing and driving to the coast.

Delving into Dance with AXIS’s Judith Smith is part of the series The Heart of It: Stories from Leaders in the Bay Area Arts Community, an EAP MADE Project. Learn more about the series by visiting the MADE page in our website.

Redesigned EAP Fellowship aims to accelerate change in the arts

/0 Comments/in Uncategorized /by Admin What are the most challenging problems facing the arts sector in the Bay Area? And what can our arts network do to tackle them?

What are the most challenging problems facing the arts sector in the Bay Area? And what can our arts network do to tackle them?

For 3 years the EAP Fellowship Program has asked these questions, each year gathering a diverse cohort of artists, advocates, and arts leaders to answer them collectively. Over the course of 9 months, the EAP Fellows engage in both dialogue and action, intended to simultaneously build their professional skills and advance the Bay Area’s arts and culture sector as a whole.

CLICK FOR FULL DETAILS AND ONLINE APPLICATION

Now in its fourth year, the EAP Fellowship has been re-designed to accelerate change in the arts. The retooled program will advance four emerging conversations:

-

Open Systems: What is the relationship between an arts organization, its mission achievement/impact, and its social and environmental context? With an increasing number of artists and arts organizations engaged in work promoting social justice, equity, and resolution of racial and socioeconomic conflicts, EAP is creating space for dialogue on cultural policies and systems that are open, responsive, transparent, and accountable.

-

Networked Approaches: Thanks in large part to new web-based tools, more arts organizations are realizing the power of networks, and rethinking how “network” and “community” relate to the purpose of their organization. EAP seeks to identify and share best practices, and collectively discover what styles of leadership are required to work in a networked way.

-

Regenerative Practices: With an under-resourced field like the arts, questions of sustainability are always paramount in the minds of arts leaders. The stress is felt not only by organizations, but by the individuals who work for and support them. EAP seeks to renew the energy and passion that drives people into the sector, and at the same time identify programs and practices that will encourage a healthier arts ecosystem.

-

Research & Development: Historically under-served, R & D activities in the arts include support for new forms, support for inquiry-based (rather than outcome-based) work, and promotion of innovative arts management practices and structures. As a new wave of innovators, investigators and entrepreneurs emerges, EAP seeks to advance an ecosystem that supports and values research and development in the arts.

The EAP Fellowship program also examines and redefines the skillset that will be required for arts leaders. In a sector where work roles are constantly evolving, EAP is exploring a more encompassing set of “hats” that arts workers must wear. EAP Fellows will explore the following four leadership roles, and will facilitate skill-sharing within their cohort:

-

Content Creators – event producers, data-driven decision makers, researchers, writers, thought leaders, action-oriented facilitators

-

Connectors – network weavers, people who forge new relationships, help discover shared values, manage communities, and whose work creates a sum that is greater than its parts

-

Visionaries – prolific communicators, compelling storytellers, strong advocates, inspiring leaders, natural innovators, lighting rods, strategic dynamos

-

Team Leaders – coaches, motivators, intrepid organizers, quality controllers, creators of systems, tacklers of complex projects, high achievers

To spur the creative juices of the group, EAP also brings in established leaders from the arts, and sometimes beyond, who share their wisdom by engaging in facilitated panel discussions and open forums. Past guests have included:

- David Cody, president, San Francisco Permaculture Guild

- Deborah Cullinan, executive director, Intersection for the Arts

- Rachel Fink, director, Berkeley Repertory School of Theatre

- Ken Foster, executive director, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

- Erica Gangsei, manager of interpretive media, SFMOMA

- Joe Goode, executive & artistic director, Joe Goode Performance Group

- Renee Hayes, associate director, Grants for the Arts / SF Hotel Tax Fund

- Heather Holt Villyard, executive director, ArtSpan

- Adam Huttler, executive director, Fractured Atlas

- Sharon Maidenberg, executive director, Headlands Center for the Arts

- Stanford School of Design (d.school)

- Marc Vogl (formerly of the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation)

- Akaya Windwood, executive director, Rockwood Leadership Institute

The EAP Fellowship’s heady mix of dynamic conversation and learning-by-doing is a unique offering, strengthened by the organization’s position as a network- and community-builder for the San Francisco Bay Area’s arts scene. The work of the Fellows, realized through public panel discussions, small group meetups and forums, publishing, and other engagement efforts, will be realized over the course of the year. The Fellowship will culminate in Emergence, the EAP annual convening and one-day conference, on Monday, June 2, 2014 in San Francisco.

Interested applicants are encouraged to apply by July 15.

Click for full details and online application

The EAP Fellowship Program was redesigned, with feedback from past participants, by the 2012-13 EAP Leadership Team: Chida Chaemchaeng (Leadership 2009-13), Bea Dominguez (Fellow 2010-11, Leadership 2011-13), Michael DeLong (Fellow 2011-12, Leadership 2012-current), Adam Fong (co-founder, Leadership 2009-11, Director 2011-current), Virginia Reynolds (Fellow 2011-12, Leadership 2012-current), and Ernesto Sopprani (Fellow 2010-11, Leadership 2011-current).

Spring Mixer

/0 Comments/in Networked Approaches, Public Program: Mixers, Public Programs, Uncategorized /by Admin

Thursday, May 9, 6:00 – 8:00 p.m.

Pro Arts

150 Frank H Ogawa Plaza

Oakland, CA 94612

FREE! RSVP via Eventbrite

You asked and we answered! We know you love our heady panel discussions and all but, perhaps even more, you love to let your hair down with us.

Come network, mingle, and explore one of Oakland’s leading galleries! Meet fellow Bay Area artists and arts sector workers over drinks and snacks at Pro Arts, and learn more about Emerging Arts Professionals (EAP). See over 400 pieces in Pro Arts’ East Bay Open Studios Preview Exhibition and enter our business card raffle for some special art prizes. Bring your cards and a desire to meet like-minded folks!

Mixer is FREE but please REGISTER HERE

Thanks to Pro Arts for hosting!

A New Look at Arts Advocacy

/1 Comment/in Uncategorized /by Admin By Alison Konecki, 2012-13 EAP Fellow

By Alison Konecki, 2012-13 EAP Fellow

In a presentation hosted by Theatre Bay Area at Shelton Studios on November 27, Margy Waller, senior fellow at the Topos Partnership, presented the findings from a research initiative designed to better understand what arguments for artistic value did and did not resonate with the general community.

A misguided approach?

When expounding upon the virtues of the arts to those not already in its passionate throes, I often default to a quantitative approach:

The arts create jobs!

The arts contribute such-and-such dollars to the GDP!

For members of a sector with largely qualitative attributes, individuals in the arts have gone to great lengths to provide quantitative data in support of their cause. It’s certainly understandable – we figure we’re being smart tacticians by engaging in the numbers and stats which are so significant to other sectors.

Go on, tell us we’re frivolous and a waste of tax dollars . . . then bam! Hit them with the good stuff.

“Perhaps you didn’t know, but for each new dollar of ‘value added’ by the performing arts industry in California, the state’s economy gains $1.38.” You smile triumphantly, holding back that well-deserved pat on the back.

Not so fast.

According to Waller, you’ve already lost the battle. Their eyes have glazed over and they’re thinking about whether it’s their turn to bring in the office donuts tomorrow.

But why? you ask. I spoke their language!

As explained by Waller, the use of economic impact facts and figures by well-meaning arts advocates is a misguided approach. The same goes for the other favorite tool in the bag of arts advocacy tricks – arts education.

Facts and figures are boring, and often do little to dispel any skepticism on the part of the listener. Arts education, while successful in inciting far more excitement in the listener, is often a tricky route to navigate. The excitement lies in the education component, leaving the arts part of the matter lying sad and forgotten in the dust.

It’s these typical non-responses or misguided responses to arts advocacy efforts that led Waller, with the Topos Partnership, to develop a research initiative aimed at determining which arguments for artistic value resonated with the general community, which did not, and which were even proving detrimental to the cause.

Surprising results

Through hundreds of talkback sessions designed to uncover what people think about a topic, rather than what they know about it, Waller found some surprising results – most notable being that “the arts” were often equated to entertainment. That in itself wasn’t terribly surprising. More surprising was the equation between the two. When viewing the arts as entertainment (a private choice), many failed to see why they were deserving of public concern and funding.

Whither arts advocacy?

If that is, indeed, the prevailing sentiment, is there even a place for arts advocacy?

Before you grow too despondent, allow me to pull you from the ledge. There is some good news. While it was true many people viewed the arts as nice but not necessary (and certainly not necessary with regard to public funding), Waller did find that there’s really no active opposition to the arts. In fact, most individuals, regardless of whether they believed the arts to be a matter of public concern, associated the arts with two specific benefits:

- The arts contribute to neighborhood vibrancy

- The arts connect people

The kicker was that even if individuals were not attending or actively participating in arts-related activities, they still believed in these two benefits.

The key, then, as Waller discovered, was to draw upon these positive associations already residing within the hearts and minds of individuals and use them to the arts advocate’s advantage.

Rather than fighting to overcome hurdles already laid out clear and menacing, why not take the path of least resistance by working with the positives and build from there? A notion revolutionary in that it’s not revolutionary at all.

Put down the stats sheet?

– Yes!

Drop the picture of children huddled over an arts and crafts table?

– Yes! Well, sort of. Pictures of children eagerly tucking into arts projects are great, as long as the pictures are within the larger frame of the arts contributing to the connecting of those children, not solely within the long-favored framework of arts education.

Shifting the conversation

The discussions framing the arts need to be shifted from the personal to the public arena. The way to achieve that shift is through the notion that creative activity sets off a ripple effect of significant benefits throughout the community, contributing to its overall vibrancy and connectedness.

In addition to shifting this framework within one’s own public relations and advocacy efforts – be it for a single organization, a local arts community, or the arts nationwide – a crucial factor in making this approach work is ensuring that your message is conveyed clearly across all channels. Often, those channels are trickling down from our friend/foe, the press.

Sure, you can’t control the press 100% of the time (ha!) but you can work with the press on a regular basis to provide them with the framework in which you’ve already carefully laid out your pro-arts messages.

When they contact you looking for an image to run with their coverage of your event, don’t send them the static picture of a playbill or the symphony hall that does little to demonstrate to the community the positive impact of your arts organization. Instead, send them the pictures of the audience mingling before the performance, or the artist chatting with a gallery patron at an opening.

Yes, you read right – no need to even show images of the orchestra/artwork/ballet; what is important is conveying how those things contribute to the vibrancy and connectedness of a community.

Of course, it isn’t merely a matter of being PR savvy. If you want your community to start thinking collectively with regard to the arts, then you have to start thinking collectively as well. Get creative! For more inspiration, and in-depth report on Waller’s findings, check out The Arts Ripple Effect.

If it’s always a fight down to the eleventh hour to get the support and funding, why not focus your efforts on shifting the community’s day-to-day mindset about the arts so that it never has to come down to the eleventh hour? Forget the stats and work with the values already in place: the arts contribute to the overall vibrancy and connectedness of a community; investment in the arts is an investment in our community.

Discussion:

What are some of the ways you have worked to advocate for the arts within your community? What worked? What didn’t?

Are you surprised by Waller’s findings? Will you adopt any of them to benefit your specific arts advocacy efforts?

About Alison Konecki

Alison Konecki is a freelance arts program and development consultant and a recent San Francisco transplant. She graduated with a B.A. in Art History and English from Canisius College in Buffalo, N.Y. and received an M.A. in Art and Museum Studies from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. During her tenure at Georgetown she spent a semester in London where she completed a course in Art and Business with a focus on contemporary art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. Prior to her move Westward, Alison was the development and community outreach coordinator for Transformer, a non-profit alternative art space in Washington, D.C., where she coordinated public programming initiatives including the organization’s Framework Panel Series, and assisted with development operations ranging from grant writing to donor cultivation. While in D.C., Alison also served as co-founder of Knowledge Commons DC – a free, self-generating “school” designed to provide non-traditional community learning and instruction.

Event Recap: Standing Room Only

/0 Comments/in Uncategorized /by AdminSuccess as we know it? It has so many definitions and variables, it’s difficult to know where to begin.

Bay Area Emerging Museum Professionals and Emerging Arts Professionals / San Francisco Bay Area thought one place to start would be an engaging conversation among those who are defining — and redefining — success in the arts regularly. On August 14, The Cartoon Art Museum welcomed the groups and a lineup of experts in the field to crack open the ideas surrounding the nebulous “success.”

Constantly Felt

The view of success can change each time a new event happens, each time new feedback is given, each time an idea is scrapped before it even makes its way to the stage. On the other hand, the view of success also changes once that email comes in with a life-changing sentiment, a production is able to continue to bring in guest artists because of record-breaking ticket sales, or the program that was a huge risk turned out to be the most popular Friday night since DIY became a household term.

As success is a measurable aspect of the art business that supports the future of museum and performing arts, and as we are still in a time of talking about the precarious “economic climate,” the topic of success will invariably be a never-ending discussion.

With all of its myriad definitions, success is contingent upon measurable results but, more important, it is dependent on fulfilling the mission and artistic vision of the organization.

Success becomes a manner of ownership, not just opinion, as each individual curator, performer, museum-goer, educator, administrator (and so on) only furthers the complexity of what success means to them and to the organizations they work for or support in other ways. Success is something shared and felt. It is something that vibrates and generates a magnetic energy.

Putting it that way highlights how vital it is for an organization to remain successful. Some key points throughout the discussion to keep an organization on track:

- Trust whomever you are working with has something to offer.

- Set your visions and voices at a high concept denominator — the lowest common denominator is not a worthy or engaging standard.

- Build credibility so you can “trade” it up later.

- Be true to your mission (and rewrite that mission whenever necessary).

If at First

Failure seems to be a buzzword that has been, well, buzzing around lately. It’s all I’ve heard since I arrived a year ago to the Bay Area. There seems to be an acceptance of failure in ways that almost mimic apology. It’s as if people are reveling in the failure/success paradigm whose benefit is perhaps a form of acceptance of the unattained. Is this counter-productive?

Gregory Stock, museum educator at Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, reminds the audience that the inherent benefit of failure is to rise to the surface. I would posit that being in a place of discomfort, and maybe even failure, are places where the real risk can take place, where fresh ideas can happen.

Annie Phillips, public relations assistant at the San Francisco Symphony and manager of Magik*Magik Orchestra, noted that failure is an opportunity to reassess and do things better the next time.

But as ODC‘s director of institutional giving Brian Wiedenmeier notes, the opposite sometimes happens: “focused on success to the exclusion of failure.” At what cost? “Everybody has sucked every now and then and we just don’t talk about it,” Wiedenmeier quips.

Rob Ready, marketing manager at ODC and co-founder of PianoFight, explained that failure is embarrassing but also humbling to talk about because it gets people to value what they do and to be more focused on putting their money where it matters.

Bottoms Up!

Without a doubt, the ubiquitous bottom line is a point of constant concern.

“The art world is afraid of money and this is a bad thing,” claims Stock and, in many ways, I would have to agree. It seems to be an unspoken need that is supposedly overshadowed by altruism. And so the success plot thickens even more. To use the proverbial bottom line again, art institutions and artists need program funding and monetary compensation to survive. In many ways, survival and longevity are forms of success.

Measuring this success requires malleability for new media outlets and maintaining the more tried and true forms of communication also. Jenna Glass, associate director of marketing at ODC, had some sound tips.

- Have a dynamic and interactive web presence that you monitor and update regularly.

- Involve yourself in social media in ways that are generative to the current programs.

- Be nimble and try new strategies.

- Know your audience (we say this all the time!) and develop niche strategies within the larger organization to build new audiences.

With that, sometimes the niche will grow into the new mission, or be a supplemental program that can help fund the other important projects. I would add, as learned from a previous blog post about place-making: talk to people, survey and chat with your audience, share your ideas with others so you can build a critical mass of ideas. Imagine the impact if several institutions were propelling similar ideas at the same time!

Meaningful Experiences

Timothy Anglin Burgard, Ednah Root Curator in Charge of American Art for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, shared an inspiring, passionate, and articulate speech challenging the audience to take a more political position and to confront mediocrity with their practice.

Museums owe it to the community to fuel ideas that generate new, valuable thought and change in the community. As so many of us are “preaching to the converted,” as Burgard stated, it is important to look beyond our comfort zones and to be in opposition to what we are used to. I would say that would apply well to anyone: as visitors to museums and each other’s projects to discussing programming ideas for future exhibitions and performances to sitting in board meetings.

Meaningful experiences are paramount to success, and everyone would benefit from a greater understanding of how to define ideas of what is meaningful to an institution and in their own personal practice.

To quote Glass earlier in the panel: “What is the story I need to tell?” Again, success is circling back to what matters, and the meaning. Or as Phillips stated, “[It’s] what gets across the footlights.”

Holly Turner began the panel with an exercise:

As a ________ I am ________ . When I work in ________ I need to have ________ and ________.

As self-affirming as it may seem, it is perhaps not something that we plainly say on a regular basis. And perhaps perhaps even more elementary, it can be a way of understanding others if put in the form of a question.

Now more than ever as artists and arts workers are being asked to wear multiple hats, new meanings for success need to be created. What seems to be at the crux of success is “the push”: push the programming and ultimately push boundaries aside and push expectations. From the grandiose to humble, success has the potential for greatness.

About Leora Lutz

Leora Lutz (http://www.leoralutz.com/index.html) is an exhibiting, interdisciplinary artist with a professional history as a writer, gallerist and art administrator. All aspects of her practice grab onto historical context, alters it, and re-presents it as a way to shift previous understanding into flux. Her work has shown at galleries, institutions and museums, including MOCA LA, Palm Springs Museum of Art, The Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, Riverside Art Museum and the Henry Project Space in Seattle. Her art and professional bibliography includes numerous critiques and profiles from The Los Angeles Times, NBC news, White Hot Magazine and LA Weekly to name a few.

Arts Management Tweet Chat on June 22 with Bea Dominguez

/0 Comments/in Uncategorized /by Admin By Michael DeLong, Managing Editor

By Michael DeLong, Managing Editor

The role artists play in creating vibrant cities seems to be the conversation du jour, inspiring lively events, provocative blog posts, and no small flurry of foundation interest. (And, perhaps most controversially for those word nerds among us, an as-yet-not-fully-recognized closed compound neologism in placemaking.)

What better time to hop on a tweet chat to discuss this very issue (that of artists as placemakers, not that of the adoption of the term) with fellow workers in the arts and culture sector?

Since April 2012, Arts Management Chat (#artsmgtchat) has been convening a community of knowledgeable, opinionated arts managers around topics such as engaging boards, emerging leaders, and social media for arts organizations. The chats happen twice a month on Fridays at 11:00 a.m. Pacific time.

On Friday, June 22, our own communications director Bea Dominguez will be hosting the tweet chat, focusing on the topic of Art and its Role in Urban Renewal. This promises to be an interesting conversation: a great way to learn more about the topic and add your own voice.

Here are just a few of the questions that Bea will be asking the tweeps:

- Are arts the precursors of vibrant cities or are they the outcome?

- Does your city value creative labor? In what ways can it value it more?

- What does it mean to you to transform a neighborhood?

See all of the questions and Bea’s inspiration for the topic on the Arts Management Chat blog.

Here’s how to participate:

- Follow the hashtag #artsmgtchat from 11:00 a.m. – noon Pacific time on Friday, June 22

- Join the TweetChat room directly for easy participation

- Spread the word to your own networks

- Ask questions and share resources ahead of the chat using the hashtag or by tweeting to @trichetriche

Never joined a tweet chat before? Don’t miss this how-to in TechSoup’s Nonprofit Social Media 101 wiki, and watch the video below.

Image: Adapted from a photo by Erik Berndt

A Change Would Do (Us) Good

/1 Comment/in Uncategorized /by Adam Fong

Changing jobs can be painful, but it might just be a service to the field.

At Grants for the Arts’ 2011 Fall Public Meeting on Leadership Issues in the Arts, Marc Vogl hit on why staff changes, particularly in leadership, are so delicate.

“The reason it’s sensitive is that it’s personal. This isn’t just a job: this is a calling, this is a career, this is a passion, this is a lifetime, this is family.”

Often the potential fallout from changing jobs can be the most powerful deterrent, whether it’s you, your colleagues, or your constituents who will bear the burden of transition. If, like me, you work in a small organization, your departure will force everyone else to adapt, and your hard-working colleagues will need to expend extra energy to integrate a new team member.

You’re not alone if you fear that the added stress could put your organization at risk, as well as jeopardize your own career.

Growing Pains

Another panelist, Michael Warr, proposed that we in the nonprofit arts sector need a “cultural reformation.” Among the many positive actions he suggested were:

- Put people (especially leaders nearing retirement) who want to leave in a good position to do so.

- Stop demanding leadership candidates meet the complete (and “ridiculous”) list of requirements that is often given in job descriptions.

- Increase appreciation for transferable skills from other roles and sectors.

- Be willing to fail, to fail faster, and to learn from failures.

Among the greatest hurdles to these changes is the underlying assumption that the field as a whole cannot grow. When there is no job growth, or when there is a recession as in 2009, we all feel trapped. Employment becomes a zero-sum game; risks become taboo. And worse, those who are already out of work have few avenues in. In that worldview, organizational change and growth are nearly impossible.

Here’s a look at the annual turnover rates in the nonprofit sector as compared to rates across all industries, distinguishing between voluntary and total turnover (data from CompData Surveys’ BenchmarkPro Survey, collected from HR departments):

The nonprofit sector has, unsurprisingly, followed the larger trend since the 2008 crash: people who do have jobs are keeping them, and the percentage of voluntary departures has dipped steeply. It’s down from 12.5 percent in 2008 to 10.4 percent in 2009, and receding below 10 percent in both nonprofit and all industries by 2010.

In other words, if you work in an organization of ten employees, on average you had one person leave last year. And — if we pretend for a moment that these figures also apply to small organizations in the nonprofit arts sector — in an organization of five employees, only one staff member has changed in the last two years.

Last fall the “rate of change” and our collective ability to “adapt” were hot topics. But if we’ve only welcomed one new voice to our team in the last two years, how fast can we really be expected to adapt?

More food for thought: In 2011, the industries with the highest voluntary turnover were hospitality, healthcare, and banking and finance. Can you guess which industries had the most growth?

It’s good for you

While considering my own job change, I came across “Four Good Reasons to Change Jobs Within the Same Industry Three Times During Your First Ten Years of Employment” by National Executive Resources, Inc. They were:

1. Changing jobs give you a broader base of experience.

2. A more varied background creates a greater demand for your skills.

3. A job change results in an accelerated promotion cycle.

4. More responsibility leads to greater earning power.

Not counting my grad school hiatus and part-time gigs, I am leaving job number two after seven years in the nonprofit arts sector. So is this why I’m leaving? To get broader experience, to become marketable to more companies, to get a promotion, and rake in the cash with my new-found “earning power”?

In a word, no.

But what if we replace the market-speak with mission-based alternatives?

experience –> knowledge

skills –> capacity

promotion –> creativity

earning –> impact

Put this way, YES, it’s why I’m leaving. I do want more knowledge and capacity, and opportunities to creatively impact the sector (in my case specifically, contemporary music).

Transitions will always be tricky, even with open communication and a well-executed hand-off. But if, like me, you want to maximize your impact (née earning power) and help the arts sector grow, changing jobs might just be a service to the field.

Image: Not So Much

EAP SF/BA Mission

OFFICE HOURS

SAT & SUN: Closed

p. (415) 209-5872